As we've seen already, some beliefs are justified by being based on or inferred from further supporting beliefs. They get their justification from the beliefs on which they're based. And those belief in turn may get their justification from other beliefs on which they're based. If we keep tracing back this chain of justification, where does it stop?

We mentioned four possibilities:

The foundationalist thinks that the chain has to stop with beliefs of this last sort, some immediately justified beliefs, which don't get their justification from any further beliefs.

Call a belief mediately or inferentially justified iff it's justified, and its justification derives in part from the justification you have for some further supporting belief, on which it is based. Call a belief immediately justified, on the other hand, iff it's justified, and your justification for believing it doesn't derive from your evidence or justification for holding other beliefs.

The foundationalist says that some of our beliefs are immediately justified, and that the justification of all our mediately justified belief can ultimately be traced back to these immediately justified beliefs.

Note that the contrast between mediate and immediate justification has to do with the source of your justification. This contrast doesn't have any direct bearing on the strength of your justification. So we should not assume without argument that immediately justified beliefs will be infallible or indubitable or anything like that.

Also note that the contrast between mediate and immediate justification is an epistemological contrast. It can't be read straightforwardly off of the facts about how psychologically immediate and spontaneous one's belief is. A belief can be psychologically immediate but still be evidentially supported by other beliefs. For example, suppose I look at the gas gauge of my car and form the belief that my car is out of gas. What happens in such a case? I may have formed a belief about the gauge, and based my belief about the car on that belief about the gauge. We can diagram that like this:

In this case it is clear that my belief that my car is out of gas is only mediately justified. But that's not the only sort of case in which we might want to talk about mediate justification. Suppose I formed my belief about the car spontaneously. I didn't rehearse any justifying argument:

to myself or others. I didn't infer my belief that the car is out of gas from other premises. I just formed that belief spontaneously and without any deliberation or inference. We can diagram that like this:

Although my belief about the car is psychologically immediate in this case, it still seems--doesn't it?--that my justification for believing it rests on my justification for believing that the gas gauge says "E". (Consider: if I were to lose my justification for believing that the gas gauge says "E", I would no longer be entitled to believe the car is out of gas--unless I acquired further evidence.) If this is right, then we should count my belief about the car as only mediately justified, even though it was formed spontaneously and we didn't go through any psychological process of inferring it from other beliefs.

Let's introduce a new distinction which will help us get clearer about this.

The distinction I need to introduce now is the distinction between reasons you have for believing P, and your reasons for believing P, the reasons that actually make you believe P. These can be different.

For example, suppose you have plenty of evidence for believing that Oswald acted alone when he shot Kennedy, but you're such a conspiracy freak that you refuse to believe it. Then one day your aunt holds a seance in which you "speak" to the dead Oswald and thereby "learn"that he did act alone. On the basis of this experience, you then believe that Oswald acted alone. In this case, you believe that P (Oswald acted alone) and you have good evidence for believing that P, but those aren't the reasons on which you base your belief. You base your belief on bad reasons. This is a case where you have good reasons for believing P, but your reasons for believing P are bad ones.

Another way to describe your belief about Oswald is to say that you have justification for believing the proposition that Oswald acted alone, but the belief you formed is not a justified belief, since it's based on bad reasons. It takes more for a belief to be justified than just for it to be a belief in some proposition you have good reasons for believing. The belief also has to be based on those good reasons. If it's based on bad reasons, then it's not a justified belief.

So now we have two notions:

Philosophers disagree about which of these notions is more basic. I think the first notion is more basic. After all, you can have justification for believing something even if you don't believe it. (Perhaps you haven't noticed that you have justification for believing it. Or perhaps you're stubborn and irrational and refuse to believe it even though the evidence supports it.) But at the moment, the important thing is just to recognize that there are these two different notions. We can leave the question of which is more basic for another day.

With the distinction between these two notions in hand, we can go back and clean up some of the things we said earlier.

When I introduced the notions of mediate and immediate justification, I talked about beliefs you actually hold. We can also define these notions for propositions you have justification for believing, without requiring that you actually believe those propositions. Let's go back to the gas gauge example. I look at the gas gauge in my car and it reads "E." So I have justification for believing that the gas gauge says "E," and that in turn justifies me in believing that the car is out of gas. Hence I have mediate justification for believing that the car is out of gas. Despite all that, I might nonetheless refuse to believe that the car is out of gas. (Perhaps I'm falsely convinced that my visual experiences are being produced by an evil demon.) We can diagram that like this:

In this case I have mediate justification for believing something, even though there isn't any mediately justified belief.

Similarly, when I introduced foundationalism, I talked about immediately justified beliefs. But all that's really crucial for the foundationalist is that you have immediate justification for believing some things. Perhaps your mind passes over those things, and doesn't actually form beliefs about them. Perhaps the beliefs you form are all about more complicated matters; hence your beliefs are all mediately justified beliefs. So long as your justification always traces back to some immediate justification, that's enough for the foundationalist. It's not essential that you actually believe all the propositions you're immediately justified in believing.

The coherentist is someone who rejects foundationalism. The coherentist denies that all our justification traces back to things we are immediately justified in believing. At a first pass, we can say that the coherentist prefers the picture where the chains of justification form big circles and loops. But that's just a first pass. It gets more complicated.

Let's introduce a technical notion. We say that a set of beliefs is coherent when they are logically consistent, and in addition they "fit together" in ways that let them explain and help support each other. So for instance, this is not a coherent set of beliefs: {P, not-P}. Neither is this: {The sun rose this morning, 2+2=4}. That's not a coherent set of beliefs because its members don't have anything to do with each other. Neither is this a coherent set of beliefs: {the most recent student I saw on campus was female, the 2nd most recent student I saw was female, the 3rd most recent student I saw was female,...,the next student I see will be male}. That set of beliefs is logically consistent. But it's not coherent, because the first n-1 beliefs don't seem to support the final belief. They support its opposite. We'd need some explanation for why I should believe that the next student will be different than all the past students. If we add in some additional explanatory belief, then we can make the set more coherent: {the most recent student I saw on campus was female, the 2nd most recent student I saw was female, the 3rd most recent student I saw was female,..., a busload of male students just pulled up to campus, the next student I see will be male}.

Another example of incoherent beliefs would be the following: {my visually-based belief that the wall is red, my belief that the wall is lit by red lights so that it would look red no matter what color it is}. These beliefs are logically consistent. The wall could be red even though it's lit by red light. And in some cases it might be possible both to know that it's red and to know that it's lit by red light. (For example, if you painted it red, and then installed the red lights yourself.) But in the present case, my belief that the wall is red is just based on looking at the wall; and my other belief tells me that looking at the wall is not a reliable way to judge its color. So this is a kind of "incoherence" in my beliefs.

Keep in mind that "coherent" and "incoherent"are technical notions. "Incoherent" doesn't carry its ordinary meaning here, of "not making sense" or being incomprehensible. My beliefs about the wall do make sense. There is some rational tension between them, and maybe it would be unreasonable to hold both beliefs at once, but they're not nonsense. When I say that my beliefs about the wall are "incoherent," I'm not saying they're nonsensical or incomprensible. I'm using the technical notion of "incoherent."

Well, this is only a sketchy picture of the notion of coherence. But it's pretty difficult to give a more substantial and precise account; so the sketchy picture will have to do for now.

Now, given this notion of coherence, there are two different ways in which you might think it affects your justification:

First, there is a negative role. This would be when incoherence among your beliefs tended to defeat or undermine those beliefs. According to this view, if you have an incoherent set of beliefs, you can't be justified in holding all of them simultaneously. You have to give up or revise some of your beliefs, until they become coherent again. This view doesn't say the facts about coherence can generate any justification; it just says they have the power sometimes to take it away.

One could also argue that facts about coherence play a positive role, that they are enough by themselves to generate justification where there was none before. So if you have a coherent set of beliefs, that's enough to make the beliefs justified. When we talk about "coherentists," we usually mean philosophers who think that coherence can play this stronger, positive role.

Another way of expressing the coherentist's position is to say that, on his view, the only sort of justification is mediate justification. Every belief that's justified has to get that justification from its relation to other supporting beliefs, that it coheres with. There are no beliefs that get their justification from "outside" your system of beliefs.

The coherentist can allow that some beliefs are psychologically immediate or spontaneous. For instance, in our earlier example of the gas gauge, I may have formed the belief that the car is out of gas spontaneously and without any deliberation or reasoning. The coherentist only insists that these beliefs all get their justification from their relation to other things one believes.

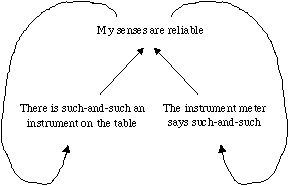

In particular, the coherentist will think that most of your perceptual beliefs about the external world get their justification in part from the fact that you're justified in believing that your senses are reliable. (The coherentist usually works with a conservative view of perception, like we saw BonJour doing.) The belief that your senses are reliable will in turn get its justification from many of your particular perceptual beliefs. So the system contains loops and circles:

The coherentist doesn't have to say that any old justificatory loop is legitimate. But he does think that some justificatory loops are legitimate, when the beliefs in question cohere together to a high degree.

There are many objections against coherentism. The most pressing objection has to do with whether the coherentist can tell any story about how a system of justfied beliefs gets input from the world. We don't want just any old consistent story with enough interlocking detail to count as justified. Alvin Plantinga tells a story of a mountain climber who's sitting on a ledge, and then all his beliefs "freeze." He keeps having new experiences, but none of his beliefs change. His friends come get him off the ledge, and take him home, but he continues to have all the same beliefs. He might now be having visual experiences of his bedroom, but he still believes he's sitting on the mountain ledge, the wind is blowing his hair, the sun is just starting to set, and so on. (We can even suppose he believes he's having experiences of the mountain ledge, the wind, the sun, and so on. But he's not. He's having experiences of his bedroom right now.) Clearly there's something wrong with this climber. We wouldn't want to count his screwy system of beliefs as justified. (Maybe it was justified once, but it's not justified anymore.) But it's hard to see how the coherentist can explain this. After all, the mountain climber's beliefs are still just as coherent as they were when he was really sitting on the mountain ledge. So the problem with them can't be that they're incoherent. We have to tell some other story about why these beliefs are unjustified. Maybe that will mean giving up coherentism.

We don't have enough time in this class to give coherentism any serious examination. I encourage you to read the optional readings on coherentism I've put on reserve in Robbins. BonJour's article "The Dialectic of Foundationalism and Coherentism" gives an especially good overview of the debate.

We will however spend the next few classes talking about what justifies our perceptual beliefs, and what makes it unreasonable for the climber to hold (or keep holding) the perceptual beliefs he does.

Foundationalism is a view with a long history. Some of the elements you find in older foundationalists' writings aren't really essential to the core ideas that we now think of as driving foundationalism. For example, the classical foundationalists tended to think:

The "foundations" or basic beliefs are infallible and indubitable.

The only ways that justification could be transmitted from the foundations to the upper-level beliefs was by strictly logical connections (so, for example, if "I have a toothache" was justified, then "Someone has a toothache" would be justified); or by a rather stingy set of inductive principles.

The "foundational" beliefs have to be beliefs about what sensations or experiences you're now having. Perceptual beliefs about the external world are fallible and defeasible, so they can't be foundational.

The classical foundationalists usually accepted the KK Principle, and an analogous principle for justification. They thought that whenever you had justification for believing P, you would have to also have justification for believing that you have justification for believing P. (We'll talk about these principles more in later lectures.)

Nowadays, most philosophers who are attracted to foundationalism advocate a more modest version of the view. Here are some differences:

The modest foundationalist just makes a claim about the source of your justification for your foundational beliefs: it doesn't come from other beliefs. This says nothing about the strength of your justification. The modest foundationalist typically allows that your immediately justified beliefs are defeasible and fallible. (So he can allow coherence to play a negative role in his epistemology: when beliefs are incoherent, that can be a way for them to be defeated.)

The modest foundationalist can allow justification to be transmitted from the foundations to the upper-level beliefs by a broader variety of ways. (He can even allow coherence to play some positive supplementary role here. He just denies that facts about coherence are ever enough, all by themselves, to make a belief justified.)

The modest foundationalist can be more open-minded about what the candidate basic beliefs are. Some modest foundationalists agree with the classical foundationalists, that our basic beliefs are all beliefs about our own sensations and experiences. Other modest foundationalists think that perceptual beliefs about the external world can also sometimes be basic.

Most contemporary foundationalists are modest foundationalists. We'll be reading Alston later; he is a modest foundationalist. (If you ever look at Alston's complete view, you'll see that it's got some reliabilist elements in it, too. So he's a "foundationalist" in the sense that some externalists are foundationalists. But the externalist element don't come up much in the Alston readings we'll be looking at. There he's just defending foundationalism.) I myself am a modest foundationalist. BonJour on the other hand is one of the major coherentists. (Well, at least he used to be. In the past few years, BonJour has had a change of heart, and decided that perhaps foundationalism is the better view after all. He mentions this in his article on "The Dialectic of Foundationalism and Coherentism." But in most of the BonJour readings we'll be looking at, he's still an arch-coherentist.)