The Blumenfelds' Defense of the Dreaming Argument

Here is David and Jean Blumenfeld's version of the dreaming argument:

- I have had dreams which were experientially indistinguishable from waking experiences. (This loosely corresponds to step 2 in our earlier formulation of the argument, when we were discussing the First Meditation.)

- So the qualitative character of my experience does not guarantee that I'm now not dreaming.

- If the qualitative character of my experience does not guarantee that I'm now not dreaming, then I can't know that I'm now not dreaming.

- So, from 2 and 3, I can't know that I'm now not dreaming. (This is step 3a in our earlier formulation of the argument.)

- If I can't know that I'm now not dreaming, then I can't know that I'm not always dreaming.

- So, from 4 and 5, I can't know that I'm not always dreaming. (This is step 3b in our earlier formulation.)

- If I can't know that I'm not always dreaming, then I can't know to be true any belief about the external world which is based on my experience. (This loosely corresponds to step 4 in our earlier formulation of the argument.)

- So, from 6 and 7, I can't know to be true any belief about the external world which is based on my experience.

The Blumenfelds defend the skeptic's argument against the following objections:

- Austin

- Kenny and Malcolm

- Moore

- The Fallibilist

- Williams

- Austin and Ryle

- The Inference to the Best Explanation Theorist

-

Austin rejects premise 1.

-

Austin denies that dreams are experientially indistinguishable from waking experiences. He argues for this as follows: we have the expression "a dream-like quality." This expression would have no use unless there was some special quality that dream experiences had and waking experiences lacked. But clearly the expression does have a use. Hence, the qualitative character of dreams must be quite different from that of waking experiences.

The Blumenfelds reply: perhaps some dreams are vague and unclear, and in virtue of this are said to have "a dream-like quality," whereas other dreams are clear and vivid. All the skeptic needs for his argument is that waking experiences are indistinguishable from dreams of the second sort. He can allow that there are also some dreams of the first sort, and that we use the expression "a dream-like quality" to describe them.

-

Kenny and Malcolm reject premise 3.

-

Kenny and Malcolm argue that it's impossible to have beliefs or make judgments when you're dreaming. So, even if the qualitative character of your experience doesn't guarantee that you're not dreaming, the mere fact that you believe you're not dreaming shows that you're not.

The Blumenfelds reply: It's very doubtful whether it's impossible to have beliefs when you're dreaming. But suppose we grant this, for the sake of argument. How does that help? To know that you're not dreaming by appeal to this fact about dreams, you'd have to be entitled to the claim that you now genuinely do believe or judge something. What entitles you to this claim? Clearly, we can at least sometimes seem to have beliefs when we're dreaming. How do you know that this isn't one of those cases? There doesn't seem to be any way in which you could know that. Hence, you can't appeal to the fact that you're now genuinely having certain beliefs to prove that you're not now dreaming.

-

Moore argues that the skeptic is not entitled to premise 1.

-

Moore says that the skeptic, in offering his skeptical argument, is at least implicitly committing himself to knowing that its premises are true. (Perhaps the skeptic doesn't say that he knows the premises to be true; but he has no business offering the argument if he doesn't know the premises to be true.) And Moore points out that, if the argument were sound, then the skeptic would not be in a position to know anything about how dreams compared to waking experiences. In particular, the skeptic would not be in a position to know premise 1:

- I have had dreams which were experientially indistinguishable from waking experiences.

The Blumenfelds reply: The skeptic can concede that he doesn't know premise 1 to be true. But in fact, the skeptic doesn't need a premise as strong as premise 1 for his argument to work. He can replace premise 1 with the weaker premise:

1*. It's possible for there to be dreams which are experientially indistinguishable from waking experiences.

and the skeptical argument goes through as before. The skeptic can claim to know that premise 1* is true, because his knowledge of 1* is not based upon perception.

-

The fallibilist rejects premise 3.

-

Premise 3 says:

- If the qualitative character of my experience does not guarantee that I'm now not dreaming, then I can't know that I'm now not dreaming.

That seems to rely on the following sort of principle:

Principle G. If you know something, then you have to have evidence that guarantees that that thing is true.

To evaluate this, let's introduce a few new terms.

We say that you're fallible about a subject matter just in case you can make mistakes about that subject matter. If you can't make mistakes, then you're infallible.

A related notion is the notion of defeasibility. The evidence you have for believing that P is defeasible just in case the verdict might change as more evidence comes in. Right now the evidence you have supports P, but as you gather more information, that support for P might be defeated. (An example of indefeasible evidence is a mathematical proof that P. Also, many philosophers think that whenever you feel pain, you have indefeasible evidence for believing that you are feeling pain at that moment. But that is controversial. Most other sorts of evidence are defeasible. For example, we have plenty of astronomical evidence that the moon is not made of blue cheese. But one can imagine a sequence of discoveries that would give us evidence making it reasonable to think that perhaps the moon is made of blue cheese, after all. So our present grounds for saying that the moon is not made of blue cheese could be defeated or overturned. They are defeasible.)

Some people think that knowledge requires infallibility and absolute certainty. They think, "Of course we can't know anything about the external world on the basis of perception. Our perceptual beliefs are all fallible and defeasible. They could be mistaken. But knowledge requires infallibility and absolute certainty. So our senses can't give us any knowledge."

That is the kind of view which is behind Principle G.

Other philosophers think that it is sometimes possible to know things on the basis of defeasible or fallible evidence. These philosophers are called "fallibilists."

Does Knowledge Require Certainty?

You could mean several different things by saying that "knowledge requires certainty."One thing you might mean by "being certain that P" is being especially confident about P, having no lingering doubts about P running through your mind. The fallibilist can allow that knowledge requires certainty in this sense.

But is it really true that knowledge requires certainty in this sense? What if you do have doubts about P running through your mind, but you recognize those doubts to be irrational and baseless? Would that prevent you from knowing P? This is not clear to me. Another thing you might mean by "being certain that P" is having really good evidence for P, evidence which is so good that there is no possibility of being wrong. This would be indefeasible evidence that P. It would be impossible for it to be defeated or overturned.

It is controversial whether knowledge requires certainty in this sense. The proponent of Principle G thinks that it does. The fallibilist thinks that it does not. We will be looking at this debate closely as the course proceeds.

One thing it's important to be clear about is that Knowledge is factive, that is, if you know that P then P has to be true.

is not enough, by itself, to settle the debate about Principle G. The claim that knowledge is factive does not entail that:

Knowledge has to be based on indefeasible, infallible evidence.

The fallibilist thinks that we can sometimes know things on the basis of fallible evidence, but he agrees that knowledge is factive. You count as knowing P on the basis of fallible evidence only if P is also true. There might be other people, whose beliefs are false, even though they're based on the same kinds of fallible evidence as yours. Their beliefs wouldn't count as knowledge.

Two Senses of "Knowledge"?

Do all of these debates, for instance between the fallibilist and the skeptic, really just reduce to a debate about how to use the word "knowledge"? Perhaps there's a loose, everyday sense of "knowledge," and a stricter, more philosophical sense of "knowledge," and we do have knowledge in the everyday sense but not in the more philosophical sense. End of story, let's go home. (And why should we care about having knowledge in the philosophical sense, anyway?)This is something we need to keep our eyes out for. Perhaps we and the skeptic are operating with different senses of "knowledge." We will discuss it as we proceed.

Stroud considers this question in his discussion. (See especially pp. 35-6, and 40-42.) He talks about someone who distorts the meaning of "There are no physicians in New York," by setting the requirements for being a "physician" absurdly high. In the same way, perhaps the skeptic's claim that "We can't know anything about the external world" only comes out true when you distort the meaning of "knowledge" into some special philosophical sense.

Stroud doesn't think that that's so. He argues that what the skeptic denies we have is just the same ordinary sort of knowledge, of the same ordinary sorts of facts, that we often claim and believe ourselves to have in everyday life. And he tries to show, in Chapter 2, that the skeptic's argument does not rest on distorting our ordinary standards or requirements for knowledge. We'll look at that discussion later. For now, we will continue to keep our eyes open. Maybe the skeptic is operating with the same notion of "knowledge" that we use in everyday discourse, maybe he isn't. We'll have to look into that.

Let's get back to our discussion of the fallibilist. The Blumenfelds concede that the argument they've presented does rest on a principle:

Principle G. If you know something, then you have to have evidence that guarantees that that thing is true.

which you wouldn't want to accept if you're a fallibilist.However, the Blumenfelds don't think that the skeptic has to appeal to such a strong principle. They think that the skeptic's argument can still go through even with a weaker principle, which the fallibilist ought to accept. So the skeptic isn't resting his whole case on a strong infallibilist construal of "knowledge." The Blumenfelds think that the skeptic's argument poses a problem for you even if you are a fallibilist.

How does the skeptic's argument work if we give up the appeal to Principle G?

The fallibilist says you can know things on the basis of evidence which merely makes those things very likely, without guaranteeing their truth. According to the Blumenfelds, the skeptic will ask: Well, how do you know it's even very likely that you're not dreaming? You would be having exactly the same experiences if you were dreaming. Those experiences don't merely fail to guarantee that you're awake. The skeptic thinks they don't give you any reason whatsoever to believe you're awake.

If you're a fallibilist, and you want to say that the skeptic is wrong, we do know we're not dreaming, we do know what the external world is like, then you'll have to find some way to resist this move that the Blumenfelds are making here. You have to argue that our experiences do give us reason to believe we're not dreaming, even though a dreaming person might have those very same experiences.

Just a Debate about How To Talk?

As I said before, when we start asking whether knowledge does or does not require infallible evidence, some people start to feel that this is just a question about how we've decided to talk. They think that whether we can "know" what the external world is like just turns on an arbitrary decision about how to use the word "knowledge." They say:Look, "knowledge" is just a word of ours. If we wanted to, we could call this state we're in right now with respect to the external world "knowledge." This is all nothing more than a debate about how to talk.

I think that is a sloppy way of thinking. Let me explain why.

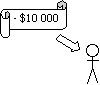

Imagine that the Bush administration decides to impose an extra $10 000/year tax on students. Only they say, let's not call it a "tax." Let's call it a "grant." That sounds nicer. (They're "granting" you a bigger debt.) Hey, what are you complaining about? The government just gave you a big grant.

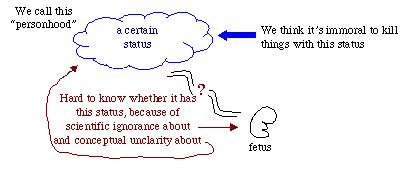

Or imagine that we're in a debate about whether abortion is moral or not, and we get to disagreeing about whether a fetus is really a person. I say, well, it's just a matter of how we use the word "person." So really the whole debate about abortion is arbitrary. If the government decides to call a fetus a "person," then it will be immoral to have abortions; if not, not.

That doesn't seem right. It seems like a better picture is this:

Now, we happen to call this status "personhood." And it is completely arbitrary that we use that word to name that status. We could easily use that word to refer to some other status, instead, if we like. But that wouldn't change the rest of the picture.

Similarly:

It doesn't seem to matter very much whether we call this a "tax" or a "grant." It would be just as bad either way.

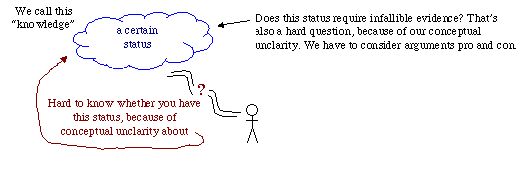

So, too, it's a matter of arbitrary convention how we use the word "knowledge." That is true. But as it happens, we use that word to pick out a certain epistemic status a person can have. And that status is very interesting to us. (Faust sells his soul to the devil in order to obtain it.)

This status--the one we in fact use the word "knowledge" to talk about--is what we're interested in, in this course. It is arbitrary what name we give to this status. We could call it "knowledge," or we could call it something else, or we could give it no name at all. The fact that it's arbitrary what name we give this epistemic status doesn't show that it's arbitrary whether someone has the status, in a given case. It will sometimes be controversial and hard to decide whether a given person has this status. That's why we have whole branches of philosophy devoted to the subject. But that just shows that the questions we're investigating are hard. Like the question whether a fetus counts as a person: that question is also hard. You should not take it to show that the questions have no answer, or that it's totally arbitrary how we answer them, one answer is just as good as another.

Let's return to our discussion of the Blumenfelds' article.

-

Williams objects to premise 5.

-

Williams points out that there's a difference between the following two claims:

- On every occasion, for all I know it is possible that I'm dreaming on that occasion.

- For all I know it is possible that: I'm dreaming on every occasion.

Compare:

- For every child, for all I know it is possible that he or she lives longer than average.

- For all I know it is possible that: every child lives longer than average.

Claim (iv) is false, but claim (iii) might nonetheless be true. Claims of form (iii) don't in general entail claims of form (iv). Similarly, Williams points out, all the skeptic has shown at step 4 is something like (i). That doesn't entail anything like (ii).

If Williams is right that the skeptic is not entitled to infer (ii) from (i), then we should reject step 5 in the Blumenfelds' argument:

- If I can't know that I'm now not dreaming, then I can't know that I'm not always dreaming.

The Blumenfelds reply: Williams is right to say that claims like (i) and (iii) do not in general entail claims like (ii) and (iv). But the skeptic can happily accept this. The skeptic doesn't think that 5 is true because claims of the one form generally follow from claims of the other form. The skeptic thinks that 5 is true because of the specific content of what it says.

Compare: Claims with the form: - X was a man.

- X must have been a cross-dresser.

Well, why then does the skeptic think that if you can't know you're not now dreaming, then you can't know that you haven't always been dreaming?

The skeptic asks, how could you acquire knowledge that you haven't always been dreaming? There are two possible ways. First, you might acquire this knowledge on the basis of empirical evidence. Second, you might acquire it by some a priori philosophical argument.

The skeptic says that the first route won't work, unless there's some time at which you can rely on your empirical evidence, some time t such that you can know at t that the empirical evidence you have then is not all just the product of a dream. But the skeptic has argued that there can be no such time. If his argument up to step 4 is sound (and if that argument works at any time t), then at no time t can you know that you're not dreaming at t. So there's no time at which you can rely on your empirical evidence. Hence, the skeptic concludes, there's no time at which you can acquire empirical evidence for believing that you haven't always been dreaming.

Perhaps, though, there's some non-empirical, a priori argument that enables you to know that you haven't always been dreaming, that you must have been awake at some point in your life. We'll consider this possibility next.

-

Austin and Ryle argue that you can know a priori that you haven't always been dreaming, because the supposition that you have always been dreaming is somehow incoherent.

-

- Austin's argument goes as follows:

- It makes sense to talk of deception (or error) only if it's possible to recognize cases of deception (or error).

- It's possible to recognize cases of deception only if there is a background of general non-deception.

- So it makes sense to talk of deception only if some experiences are non-deceptive.

The Blumenfelds reply: Why should we accept premise (i)? Austin seems to be assuming that the claim "Belief B is erroneous" makes sense only if it's possible to tell whether the claim is true. The verificationist accepts that. The verificationist believes that if it's not possible to tell whether a certain claim is true, then the claim is meaningless. But if we haven't already been persuaded to accept verificationism, then it's unclear why we should accept Austin's premise (i).

- It makes sense to talk of deception (or error) only if it's possible to recognize cases of deception (or error).

- Ryle argues that in order for counterfeit coins to exist, there must also exist some real coins. He apparently intends this as an analogy for our sense-experiences: in order for some experiences to be dreams, some experiences must be veridical.

The Blumenfelds reply: First, even if we accepted Ryle's argument, it's unclear whether the argument would establish that any of your experiences are veridical. Perhaps, in order for some experiences to be dreams, somebody somewhere has to have veridical experiences. But that doesn't show that you do.

Second, it's not at all clear that in order for counterfeit coins to exist, there must also exist some real coins. The Blumenfelds tell the following story:

Just as the first money is about to be printed, a band of criminals seizes the press and issues its own currency, which is a facsimile of the original design. Later, when the shady origins of the currency are exposed, the community forever drops the institution of money.

In such a situation, it would appear that all the money that has ever existed has been counterfeit.

- Austin's argument goes as follows:

-

Perhaps the best explanation of your having the experiences that you do is that you're not dreaming but awake.

-

Sometimes you're justified in believing P because P is part of the best explanation of some observed evidence. For instance, suppose you remember you left the headlights on your car on. Now the headlights are off, and the radio doesn't work. Furthermore, when you turn the key nothing happens. What is the best explanation of all this evidence? The best explanation is that the car's battery has died. There are other possible explanations: for instance, maybe a Good Samaritan broke into the car and turned off the headlights. But then some mischievous kids also broke into your car and disconnected the wires leading to the radio and the starter engine. That is all possible. But the best explanation of what happens seems to be: the lights were on all night, and now the battery is dead. So that's what you seem to be justified in believing.

Perhaps you're justified in believing that there's an external world in something like the same way. Perhaps the hypothesis that there's an external world which you sometimes perceive is part of the best explanation of why you have the experiences that you do.

This is an attractive line of response to the skeptic, and it's one that many contemporary philosophers accept. We'll look again at this line of response later in the course, when we discuss coherentism.

The important question a fan of this response has to address is: Why is the hypothesis that we sometimes perceive an external world a better explanation of our experiences than any of the skeptical alternatives?

Slote offers an answer to this question. His answer is that the skeptical hypotheses are "inquiry-limiting" hypotheses, and that insofar as you're an inquirer after truth, it's reasonable to avoid accepting inquiry-limiting hypotheses.

The Blumenfelds reply: That may be so, but how do we know that it's epistemically reasonable to avoid accepting inquiry-limiting hypotheses? Perhaps it's merely practically reasonable to avoid the skeptic's hypotheses, given that we an interest in continued inquiry. That doesn't show that the skeptic's hypotheses are any worse off epistemically.

URL: http://www.courses.fas.harvard.edu

Last Modified:

Copyright © The President and Fellows of Harvard College