Our connecting theme for this segment of the class will be how we can have different explanations in terms of mental states (your body ended up in the kitchen because you wanted a phone charger and you believed the only charger left in the house was in the kitchen…) versus explanations in terms of brain firings and muscle contractions. What relation do these different explanatory structures have to each other?

An idea emphasized in the Hofstadter dialogue was that the patterns at one level can be different from patterns at other levels, and can be difficult to see if you’re not looking at the right level. Thus, in his story the Anthill has one kind of political view while the little ants that make her up have different social preferences. The Anthill is friends with the Anteater, while the little ants are terrified of him. And so on.

This is reminiscent of Leibniz’s analogy of the mill back from the van Inwagen reading at the start of term. From p. 158 of that reading:

[W]e can find this notion — the notion of a physical thing having thoughts and sensations — very puzzling. There is a famous passage in Leibniz’s Monadology that very clearly brings out the puzzling aspects of this notion:

Furthermore, we must admit that perception, and whatever depends on it, cannot be explained on mechanical principles, i.e. by shape and movements. If we pretend that there is a machine whose structure makes it think, sense and have perception, then we can conceive it enlarged, but keeping to the same proportions, so that we might go inside it as into a mill. Suppose that we do: then if we inspect the interior we shall find there nothing but parts which push one another, and never anything which could explain a perception. Thus, perception must be sought in simple substances, and not in what is composite or in machines.

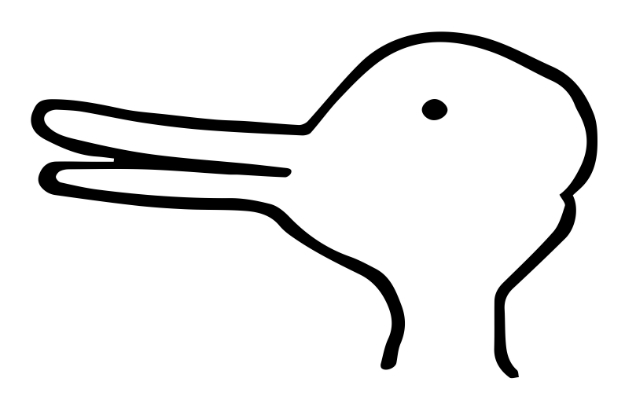

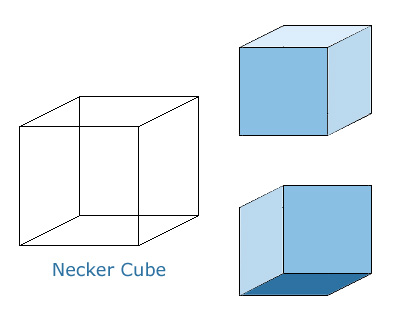

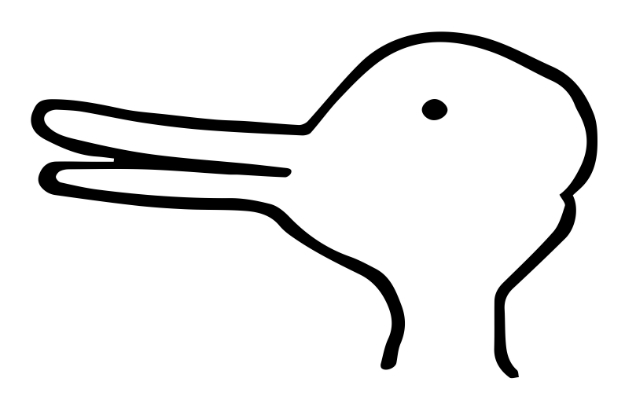

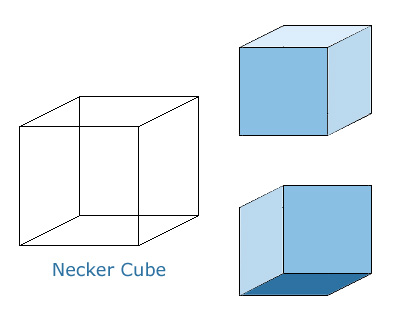

Other examples of this we mentioned are how you might read some text and take in its meaning, without noticing what font the text was written in, or that some words were abbreviated or misspelled, or perhaps even (if you’re fluent in multiple languages) what language the text used. Also the duck/rabbit drawing and the Necker cube, which can each be “seen” in different ways, but when you look at it one way, that makes it hard or impossible to see it the other way at the same time.

Broad’s paper about Emergentism versus “Mechanism” distills this picture into a more definite philosophical thesis. The kind of “Mechanistic” view Broad opposes says that the laws of psychology (and chemistry and biology) are “just the compounded results of”

a few kinds of physical particles obeying a few simple elementary laws. One kind of contrasting position would say that entities that have mental or chemical or biological properties need instead to have a special ingredient or substantial component. (Broad discusses “entelechies” as hypothesized ingredients that make life possible, in the way we discussed Descartes thinking that “souls” made mentality possible.) That’s not the view Broad takes. Instead, he favors a third position, that he calls Emergentism. This says that even if the physicists correctly identify all the kinds of particles or elementary substances there are in the world, still the properties discussed by psychology, chemistry, and biology “could not even in theory be deduced from the most complete knowledge”

of how the world is arranged at the level of physics.

Here is Broad making that case for the example of chemistry (p. 110):

Oxygen has certain properties and Hydrogen has certain other properties. They combine to form water, and the proportions in which they do this are fixed. Nothing that we know about Oxygen by itself or in its combinations with anything but Hydrogen would give us the least reason to suppose that it would combine with Hydrogen at all… And most of the chemical and physical properties of water have no known connexion, either quantitative or qualitative, with those of Oxygen and Hydrogen. Here we have a clear instance of a case where, so far as we can tell, the properties of a whole composed of two constituents could not have been predicted from a knowledge of the properties of these constituents taken separately, or from this combined with a knowledge of other wholes which contain these constituents.

Broad goes on to say that it may be that the chemical facts are “determined by” the physical properties of the constituents (p. 110; he means here something like supervenience, though that word wasn’t yet being used at the time). What’s crucial is that no one could deduce or predict the chemical behavior from the more basic physics. And he thinks this is true about how biology and psychology are related to physics too. No one can predict from a description of the physical reactions and the structure of your brain, that when you look at a red apple you’ll have an experience like this. (We’ll come back to this idea in readings later in the term.)

Contemporary theorists will regard Broad’s suggestions about chemistry and biology as much more dubious today than they did when he wrote his book (1925). The way I was taught chemistry in school, it was framed as though indeed if you know enough about the detailed physical properties of Oxygen and Hydrogen, you would be able to deduce that they can combine and what the chemical behavior of their combination was. They’d grant that some of these higher-level (chemical) behaviors might be surprising consequences of the lower-level, physical facts; and hard to see if you just focused on the patterns studied by physicists. But they’d disagree with Broad’s claim that it would be impossible to predict them from the physics.

Still, Broad may be right about the relation between psychology and physics, even if it turns out he’s wrong about biology and/or chemistry.

Some interesting aspects of Broad’s paper.

As we’ll discuss later, words like “reduce” and “reductionism” can mean different things in different conversations. Broad doesn’t himself use these words very often. But what he describes (as his Mechanist opponent) is one central paradigm of a Reductionist picture of the relation between mental and physical.

As we mentioned above, Broad does think that chemical facts supervene on the physical facts. So the anti-Reductionist view he favors is still compatible with accepting a kind of supervenience. It’s also compatible with rejecting supervenience. In the case of the relation between the mental and the physical, I think Broad doesn’t explicitly choose. He does commit to a denial that there are any special mental substances.

Broad is willing to accept that there may be laws connecting the mental and the physical. What the Reductionist adds to that, and he resists, is that there will be a few simple laws from which everything else follows. All that Broad is willing to allow is that there may be a “plurality of irreducible” laws, none of which could be predicted from the others. (As in his suggestion above that you’d need different laws for how Oxygen combines with Hydrogen, and how it combines with Carbon, and so on.)

Consider this quote from p. 112:

We should merely have to recognize… that we are dealing with a unique and irreducible law; and not with a special case which arises by the substitution of particular values for variables in a more general law, or with a combination of several more general laws.

Or this quote from p. 115. Broad is calling a law that connects different levels like physics and mentality a “trans-ordinal” law:

There is nothing, so far as I can see, mysterious or unscientific about a trans-ordinal law… A trans-ordinal law is as good a law as any other; and, once it has been discovered, it can be used like any other to suggest experiments, to make predictions, and to give us practical control over external objects. The only peculiarity of it is that we must wait till we meet with an actual instance of an object of the higher order before we can discover such a law; and that we cannot possibly deduce it beforehand from any combination of laws which we have discovered by observing aggregates of a lower order… We could not possibly have formed the concept of such a color as blue or such a shade as sky-blue unless we had perceived instances of it, no matter how much we had reflected on the concept of Color in general or on the instances of other colors and shades which we had seen. It follows that, even when we know that a certain kind of secondary quality (e.g., color) pervades or seems to pervade a region when and only when such and such a kind of microscopic event (e.g., vibrations) is going on within the region, we still could not possibly predict that such and such a determinate event of the [microscopic] kind… would be connected with such-and-such a determinate shade of color (e.g., sky-blue).