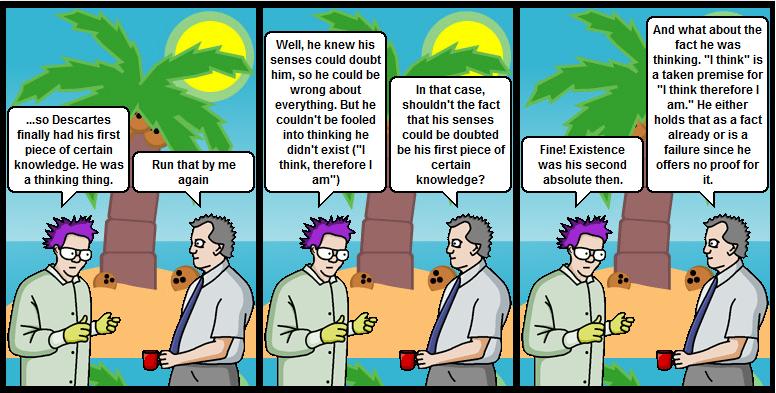

So Descartes’ problem is this. How can he be sure that any of his beliefs are true? Perhaps everything he perceives is really just an illusion, like in a dream or in The Matrix. Or maybe God or an evil demon is trying to deceive him as fully as possible. How could he tell? How can Descartes be sure that anything he believes is true, so long as those are open questions?

In Meditation 2, Descartes thinks he finds a belief which is immune to all doubt. This is a belief he can be certain is true, even if he is dreaming, or God or an evil demon is trying to deceive him as fully as possible.

What is it?

Here is what Descartes says:

…I have convinced myself that there is absolutely nothing in the world, no sky, no earth, no minds, no bodies. Does it not follow that I too do not exist? No: if I convinced myself of something then I certainly existed. But [suppose] there is a deceiver of supreme power and cunning who is deliberately and constantly deceiving me. In that case too I undoubtedly exist, if he is deceiving me; and let him deceive me as much as he can, he will never bring it about that I am nothing so long as I think that I am something. So after considering everything very thoroughly, I must finally conclude that this proposition, I am, I exist, is necessarily true whenever it is put forward by me or conceived in my mind.

There are two ways to interpret Descartes’ argument here.

According to the first interpretation, Descartes is arguing as follows:

Contrast the argument: “I walk. If I walk, then I exist. Hence, I exist.” Would that be just as good an argument for Descartes purposes? Why not?

Descartes is better off using the argument 1-2-3 than the argument about walking. But even the argument 1-2-3 has some difficulties, at least as an interpretation of what Descartes actually writes. One problem with this account of Descartes’ argument is that, if this were his argument, we’d expect him to say that the first indubitable proposition is “I think.” But that’s not what he says. The first proposition he seems to regard as indubitable is the proposition “I am, I exist.”

In addition, if this were Descartes argument, he’d owe us an account of why he is entitled to appeal to the premise “I think.” Descartes doesn’t offer any argument for the premise that he is thinking. Maybe he could have argued for such a premise; he might have argued that a person can always tell what he’s thinking. But in fact we don’t find him giving any such argument. Nor does he give us any argument for the premise that “Whatever thinks, also exists.” Again, maybe he could have argued for such a premise; but there’s no passage in the text where he’s obviously giving such an argument.

For these reasons, it seems that 1-2-3 does not exactly represent Descartes’ reasoning.

Here’s a second, slightly different interpretation of how Descartes is arguing here. He could be arguing like this:

This interpretation avoids the two problems that the first interpretation faces. In addition, it seems to better account for the wording of Descartes’ conclusion:

This proposition, I am, I exist, is necessarily true whenever it is put forward by me or conceived in my mind.

It’s not a perfect interpretation. But it does seem to be a little bit closer to what Descartes actually says.

Now, you might agree that this is what Descartes said, but still have objections to the argument. That’s good, you should be thinking about these arguments critically. But be sure to keep in mind that when we’re dealing with a philosopher’s text, we have two tasks. One task is to figure out what the philosopher’s argument is. That won’t always be straightforward. Sometimes there will be more than one possible interpretation, and we’ll have to figure out which one makes the best sense of what the philosopher actually wrote. The second task is to philosophically assess the argument, to criticize it or defend it against criticism. These tasks are not completely independent from each other. But they are separate tasks. What we’ve been trying to do here is to figure out what Descartes said, and why.

If you want to read more about the Cogito argument, you can begin with this Wikipedia entry (but, as with Wikipedia entries in general, and also philosophy articles in general, don’t expect everything said there to be uncontroversial). There are links to further resources at the end of the Wikipedia page.

At this point, Descartes now takes himself to be reasonably certain that he exists. But he’s not sure what kind of thing this “I” is, that he’s sure exists. He writes:

But I do not yet have a sufficient understanding of what this “I” is, that now necessarily exists. So I must be on my guard against carelessly taking something else [other than myself] to be this “I”… I will therefore go back and meditate on what I originally believed myself to be… I will then subtract anything capable of being weakened, even minimally, by the arguments now introduced, so that what is left at the end may be exactly and only what is certain and unshakeable.

What then did I formerly think I was?… The first thought to come to mind was that I had a face, hands, arms… the body. The next thought was that I was nourished, that I moved about, and that I engaged in sense-perception and thinking; and these actions I attributed to the soul…

He reflects a bit on what he formerly understood a soul to be, and what he understood a body to be. Then he returns to his project of setting aside any of his former beliefs that he’s not yet sure are true:

But what shall I now say that I am, when I am supposing that there is some supremely powerful and…malicious deceiver, who is deliberately trying to trick me in every way he can? Can I now assert that I possess even the most insignificant of the all the attributes which I have just said belong to the nature of a body? […He says no…] But what about the attributes I assigned to the soul? […Things don’t look so good here, either, for example:] Sense-perception? This surely does not occur without a body, and besides, when asleep I have appeared to perceive through the senses many things which I afterwards realized I did not perceive through the senses at all…

But now Descartes hits upon something. The last property he attributed to a soul is thinking, and the Cogito argument earlier in Meditation 2 persuades him that this is not a property which he should doubt he has. Here is the key passage. I insert some markers (D1)-(D7) to enable us to refer back to crucial pieces of the passage. The markers come in a funny order (and I skip D2 and D3); we’ll see why as we proceed. “D” here means “from Descartes’s text.”

Thinking? At last I have discovered it — (D6) thought: this alone is inseparable from me. (D1) I am, I exist — that is certain. (D4) But for how long? For as long as I am thinking. (D5) For it could be that were I totally to cease from thinking, I should totally cease to exist. At present, I am not admitting anything except what is necessarily true. (D7) I am, then, in the strict sense only a thing that thinks; that is, I am a mind, or intelligence, or intellect, or reason… I am a thing which is real and which truly exists, But what kind of thing? As I have just said — a thinking thing.

Okay. What is going on here?

I’m going to invite you to consider a couple of claims, which are in the neighborhood of things Descartes says, and may in some cases be exactly what Descartes said, but we’re going to begin by just getting clear on what these claims mean, before trying to settle which ones Descartes committed himself to. I’ll label these claims (H1)-(H6). “H” for “hypothesis.”

Descartes does know these to be true; that’s part of what he says in D1. (D1 is not the same as H1. D1 says not that H1 is the case, but rather that Descartes is certain that H1 is the case.)

Not only do H1 and H2 seem to be true and known by Descartes to be true: as he begins the next stage of his argument, all he can be absolutely certain of is that he exists, and that he is able to think and doubt. He does not yet know that he has a body. (But neither does he know yet that he lacks a body.)

In addition to H1 and H2 and D1, let’s also put on the table two further claims about Descartes’ knowledge of claims H1 and H2:

These are different claims from H1 and H2, and different also from the claim that Descartes knows H1 or H2. Claim H3 says that that’s all he knows right now; he doesn’t know anything else. Claim H4 says something about when he’s in a position to know claim H1.

Although these are new claims, these also seem to be claims that Descartes should be allowed to rely on at this stage in his discussion.

Now let’s consider some stronger claims about the relation between existence and thinking:

What this means is that thought is a property which it’s impossible for me to exist without — in the same way that it’s impossible for a square to exist without having four sides. I could not possibly exist without thinking. If I were to stop thinking, then I would stop existing. So according to claim H5, a certain kind of deep sleep is impossible. It is impossible for me to exist though a period during which I am sleeping so deeply that no thought is taking place.

Does this follow from any of the claims we’ve considered so far? From H1 or H2? From D1? From H3 or from H4?

It should be clear that claim H5 does not follow from claim H1 or H2. It’s trickier to see that it doesn’t follow from the other claims. The following example may help make it clear why claims of form H5 don’t in general follow from claims of form H3 and H4:

Similarly, the fact that it’s only when Descartes is thinking that he can know for certain that he exists, and the fact that all Descartes knows for certain about himself is that he exists and sometimes thinks, do not show that it’s only when Descartes is thinking that he really exists. They do not show that it would be impossible for Descartes to exist through a period when no thinking takes place (for example, a period during which he’s sleeping very deeply).

Hence, we see that claims H3 and H4 are not by themselves enough to establish claim H5:

What about this further claim?

Even if claim H5 were correct, that would not show that claim H6 is correct. The mere fact that thought is one of my essential properties would not by itself show that I have no other essential properties.

So H5 is a more ambitious claim than any of H1, H2, D1, H3, or H4, and might be false even if the preceding claims are true; and H6 is yet a further claim, and might be false even if H5 were true.

Let’s look back at Descartes discussion. It’s a bit convoluted, and we have to be careful how we tease it apart.

Thinking? At last I have discovered it — (D6) thought: this alone is inseparable from me. (D1) I am, I exist — that is certain. (D4) But for how long? For as long as I am thinking. (D5) For it could be that were I totally to cease from thinking, I should totally cease to exist. At present, I am now admitting anything except what is necessarily true. (D7) I am, then, in the strict sense only a thing that thinks; that is, I am a mind, or intelligence, or intellect, or reason… I am a thing which is real and which truly exists, But what kind of thing? As I have just said — a thinking thing.

D6 is the same as our claim H6, and this seems to be what Descartes is arguing for in this passage. D7 seems to be a restatement of D6. The text in between D6 and D7 seems to be the reasons that Descartes is presenting for that conclusion H6/D6/D7.

D1 is clear enough.

What is going on in D4?

But for how long? For as long as I am thinking.

There are two ways to interpret this. On the first interpretation, Descartes is saying that he exists only while is he is thinking. This would essentially be claim H5, that thought is essential to Descartes. We haven’t yet seen any reason we should believe this. Moreover, the next passage, D5, seems to say, not that Descartes definitely would cease to exist, when he ceases thinking; but only something weaker, namely that for all Descartes knows, that may be the case.

So it seems to me more more likely that we should interpret Descartes differently here. What he is saying in D4 could instead be: it is certain that he exists, but for how long is that certain? Not: for how long does he exist? But rather: for how long is it certain that he exists? Descartes answer is that it is certain that he exists only when he is thinking. When he is not thinking, then maybe he exists, and maybe he does not. At this point in his argument, he’s not yet in a position to know. This sounds like our claim H4.

But now Descartes continues:

(D7) I am, then, in the strict sense only a thing that thinks; that is, I am a mind, or intelligence, or intellect, or reason… I am a thing which is real and which truly exists, But what kind of thing? As I have just said — a thinking thing.

And as we said, this sounds like a restatement of D6, which is the conclusion Descartes is aiming for, and is our thesis H6.

So what have we got here?

The argument starts with D1, which seems harmless enough. Then there is a passage (D4) which could be interpreted in two ways: one way interprets it as our thesis H5, which is close to (though not quite the same as) the intended conclusion H6. The other ways interprets it as our thesis H4, which is harmless enough. Then we get the conclusion, which we called H6 and which Descartes seems to state in both passage D6 and in D7.

It doesn’t matter how you turn this around, it doesn’t seem like a good argument. It wouldn’t help if D4 is interpreted as thesis H5, because as we said, in the first place, Descartes hasn’t given any reasons to believe that thought is not merely a property he happens now to have, but also a property that’s essential to him. And in the second place, thesis H5 falls short of what Descartes is trying to establish: even if thought is essential to him, it might not be the only property that’s essential to him. Perhaps some bodily properties are also essential to him. Perhaps some bodily properties are what thought is. He’s not yet in any position to know that that’s so; but neither is he yet in a position to know that it isn’t so.

Descartes is a smart guy. He is fully aware that the argument we just looked at is deficient. He believes that claims H5 and H6 are true. But at the bottom of the page, he grants that he hasn’t yet proven that those claims are true. He’s going to come back to them later, and present another, more thought-out, argument for them. That’s in Meditation 6, which we’ll look at next. Here’s where Descartes acknowledges that he hasn’t proven that H5 and H6 are true. He raises the question:

…And yet may it not perhaps be the case that these very things which I am supposing to be nothing, because they are unknown to me, are in reality identical with the “I” of which I am aware?

In other words: couldn’t it be the case that what Descartes really is is just a body that thinks? It’s just that, at this stage of the argument, he only knows that he’s a thinking thing, and doesn’t yet know that he is also a body.

Descartes answers the question:

I do not know, and for the moment I shall not argue the point, since I can make judgments only about things which are known to me…

Here Descartes is retracting claim H6. He admits that at this stage in the argument, he’s not in a position to know whether he is identical to his body or distinct from it.