Philosophy has a lot to do with arguments. It’s about giving arguments and it’s about evaluating or critically examining other people’s arguments to determine how good they are, and sometimes objecting to or resisting those arguments, or defending them against other people’s objections.

A philosophical argument is not the same thing as a quarrel; it (ideally and usually) won’t involve screaming abuse, making threats, or throwing things. The goal of an argument is not to attack your opponent, or to impress your audience. Its goal is to offer good reasons in support of your conclusion, reasons that all parties to your dispute can accept.

Neither is an argument just the denial of what the other person says. Even if what your opponent says is wrong and you know it to be wrong, to resolve your dispute you have to produce arguments. And you haven’t produced an argument against your opponent until you offer some reasons that show him to be wrong.

Fundamentally, an argument is some reason (or several reasons) offered in support of a conclusion.

An important thing to remember is that even if a given argument is bad, its conclusion might still be true! So just because we criticize or object to some argument, does not mean that we’ve thereby refuted its conclusion. We’re just saying that argument doesn’t give good reasons for the conclusion. There may be other, better arguments that do. It may even be a conclusion that we ourselves want to accept.

When you’re arguing, you’ll usually take certain theses for granted (these are the premises of your argument) and attempt to show that if one accepts those premises, then one ought also to accept the argument’s conclusion.

Here’s a sample argument. The premises are in red.

In this argument, it’s clear what the premises are, and what the conclusion is. Sometimes it will take skill to identify the conclusion and the premises of an argument. The conclusion won’t always come last; sometimes it may instead be announced first. Rarely, it might even occur in the middle.

Sometimes an argument will have several conclusions — some of them will be intermediate steps on the way to the argument’s main conclusion. Or there may be a main conclusion that the argument is primarily trying to establish, and then several further consequences the author claims follows from that main conclusion.

You will often have to extract an argument’s premises and conclusion(s) from more complex and lengthy passages of prose. When you do this, it is helpful to look out for certain key words that serve as indicators or flags for premises or conclusions.

Some common premise-flags are the words because, since, given that, and for. These words usually come right before a premise. Here are some examples:

Your car needs a major overhaul, for the carburetor is shot.

Given that euthanasia is a common medical practice, the state legislatures ought to legalize it and set up some kind of regulations to prevent abuse.

Because euthanasia is murder, it is always morally wrong.

We must engage in affirmative action, because America is still a racist society.

Since abortion is a hotly contested issue in this country, nobody should force his opinion about it on anyone else.

Some common conclusion-flags are the words thus, therefore, hence, it follows that, so, and consequently. These words usually come right before a conclusion. Here are some examples:

You need either a new transmission, or a new carburetor, or an entirely new car; so you had better start saving your pennies.

Affirmative action violates the rights of white males to a fair shake; hence it is unjust.

It is always wrong to kill a human being, and a fetus is undoubtedly a human being. It follows that abortion is always wrong.

A woman’s right to control what happens to her body always takes precedence over the rights of a fetus. Consequently, abortion is always morally permissible.

Euthanasia involves choosing to die rather than to struggle on. Thus, euthanasia is a form of giving up, and it is therefore cowardly and despicable.

As we said, the premises are what the author takes for granted and relies on, in order to establish something else. Sometimes they will be observations about specific facts; other times they may be general principles. We’ll discuss what it takes for an author to be entitled to their premises below.

Authors don’t always state all the premises of their arguments. Sometimes they rely on certain premises implicitly. It will take skill to identify these hidden or unspoken premises. We’ll discuss this more below, too.

Arguments come in different flavors.

The most important category for our discussion will be deductive or demonstrative arguments. As philosophers use these labels, this means arguments structured so that if their premises are true, their conclusion also has to be true. Mathematical proofs are good examples of this. Most of the arguments philosophers concern themselves with are also — or purport to be — arguments of this flavor.

Ordinarily, we talk about Sherlock Holmes “deducing” certain things, but most of his reasoning doesn’t count as “deductive” in that philosopher’s sense. Neither are most of the arguments we employ in everyday life deductive arguments. They aren’t attempts to prove a thesis conclusively. Instead, they just cite evidence, and provide reasoning, that tries to make their conclusion plausible, or reasonable to believe, or show that it’s probably true. Such arguments can still sometimes be good — in the sense that a reasonable person may find them persuasive or compelling.

Some examples include: concluding that it won’t snow on June 1st this year, because it hasn’t snowed on June 1st for any of the last 100 years; concluding that your friend is jealous because that’s the best explanation you can come up with of his behavior; and so on.

Philosophers have different labels and ways of categorizing these non-deductive arguments. You may see the labels “inductive,” and/or “ampliative,” and/or “inference to the best explanation,” or others. It’s controversial and difficult to know what qualities make such arguments good. Fortunately, we don’t need to concern ourselves with those questions. These non-deductive arguments won’t play a large role our (or in many other) introductory philosophy courses. We’ll mostly work with deductive arguments.

Whether a deductive argument should convince us depends wholly on whether we accept its premises, and whether its conclusion follows from those premises. So when we’re evaluating such an argument, there are two kinds of question to ask:

and:

These are completely independent issues. Whether or not to accept an argument’s premises is one question; and whether or not its conclusion follows from its premises is another, wholly separate question.

If we don’t accept the premises of an argument, we don’t have to accept its conclusion, no matter how clearly the conclusion follows from the premises. Also, if the argument’s conclusion doesn’t follow from its premises, then we don’t have to accept its conclusion in that case, either, even if the premises are obviously true.

So bad arguments come in two kinds. Some are bad because their premises are false; others are bad because their conclusions do not follow from their premises. (Some arguments are bad in both ways.)

Let’s consider our sample argument again:

In this argument, the conclusion does in fact follow from the premises, but at least one of the premises is false. It’s not true that one has to pay tuition in order to receive a UNC degree. (For example, UNC sometimes gives out honorary degrees to people who were never UNC students, and never paid tuition.) Probably the other premise is false, too: as far as I know, Shoeless Joe Jackson did not ever receive a UNC degree.

So this argument does not, by itself, establish that Shoeless Joe Jackson paid tuition to UNC.

If we recognize that an argument is bad, it should lose its power to convince us. As we mentioned before, that doesn’t mean that an argument’s being bad gives us reason to reject its conclusion. The bad argument’s conclusion might after all be true; it’s just that the bad argument gives us no reason to believe the conclusion is true.

Philosophers use some special terminology to describe the qualities that make a deductive argument good.

We call an argument deductively valid (or, for short, just “valid”) when it has the right kind of structure, so that its conclusion logically follows from, or “is implied or entailed by,” its premises.

Terminology: The Philosophical Glossary warns about being careful to only call inferences and arguments “valid”:

In philosophical discussions, usually only inferences or arguments can be valid… Not points, objections, beliefs, questions, or worries…

For points and beliefs and statements, what you probably want to say is that they’re true (or false). Or that they’re justified or well-supported (or undefended or controversial).

In our courses, don’t call a statement “valid”… Don’t call an inference or an argument “true.”

The Glossary also has tips about when to say “imply/entail” and when to say “infer.”

Validity is a property of an argument’s form. It doesn’t matter what the premises and the conclusion actually say. It just matters whether the argument has the right structure. So, in particular, a valid argument need not have true premises, nor need it have a true conclusion. The following is a valid argument:

Neither of the premises of this argument is true. Nor is the conclusion. But the premises are of such a form that if they were both true, then the conclusion would also have to be true. Hence the argument is valid.

To tell whether an argument is valid, figure out what the form of the argument is, and then try to think of some other argument of that same form and having true premises but a false conclusion. If you succeed, then every argument of that form must be invalid. A valid form of argument can never lead you from true premises to a false conclusion.

For instance, consider the argument:

This argument is of the form If P then Q. Q. So P.

(If you like, you

could say the form is: If P then not-Q. Not-Q. So P.

For present

purposes, it doesn’t matter.) The conclusion of the argument is true.

But is it a valid form of argument?

It is not. How can you tell? Because the following argument is of the same form, and it has true premises but a false conclusion:

Since this second argument has true premises and a false conclusion, it

must be invalid. And since the first argument has the same form as the

second argument (both are of the form If P then Q. Q. So P.

), both

arguments must be invalid.

| Here are some more examples of invalid arguments: | |

|---|---|

| The Argument | Its Form |

I. If there is a hedgehog in my gas tank, then my car will not start. |

If P then Q. Q. So P. |

II. If I publicly insult my mother-in-law, then my wife will be angry at me. |

If P then Q. Not-P. So not-Q. |

III. Either Athens is in Greece or it is in Turkey. |

Either P or Q. P. So Q. |

IV. If I move my knight, Christian will take my knight. |

If P then Q. If R then Q. So if P then R. |

If an argument aims to be deductive, but is invalid, it won’t give us any reason to believe its conclusion. (Though, as we said, it may be that the conclusion nonetheless happens to be true.)

If you take a class in Formal Logic, you’ll study which forms of argument are valid and which are invalid. We won’t devote much time to that study in this class. I only want you to learn what the terms “valid” and “invalid” mean, and to be able to recognize a few clear cases of valid and invalid arguments when you see them.

| For each of the following arguments, determine whether it is valid or invalid. If it’s invalid, explain why. |

I. Your high idle is caused either by a problem with the transmission, or by too little oil, or both. |

II. If the moon is made of green cheese, then cows jump over it. |

III. Either Colonel Mustard or Miss Scarlet is the culprit. |

IV. All engineers enjoy ballet. |

As we mentioned before, sometimes an author will not explicitly state all the premises of his argument. There’s something he needs to be assuming, but he hasn’t identified it and labeled as a premise. This will render the author’s argument invalid as it is written. But if it’s clear what the author meant or needs to be relying on, we can often “fix up” the argument by supplying that missing premise. For instance, as it stands, the argument:

is invalid. But it’s clear how to fix it up. We just need to supply the implicit premise:

You should become adept at filling in such missing premises, so that you can see the underlying form of an argument more clearly.

| Try to supply the missing premises in the following arguments: |

I. If you keep driving your car with a faulty carburetor, it will eventually explode. |

II. Abortion is morally wrong. |

Sometimes a premise is left out because the author takes it to be obvious, as in the engineer argument and the exploding car argument. But sometimes the missing premise is very contentious, as in the abortion argument. In these cases, the author may not yet recognize that they’re relying on the assumption. Or they may not appreciate how contentious it is. Occasionally, they may realize these things, but just hope they can trick their readers into not noticing.

An argument is sound just in case it’s valid and all its premises are in fact true.

The argument:

is an example of a valid argument which is not sound.

We said above that a valid argument can never take you from true premises to a false conclusion. So, if you have a sound argument for a given conclusion, then, since the argument has true premises, and since the argument is valid, and valid arguments can never take you from true premises to a false conclusion, the argument’s conclusion must be true. Sound arguments always have true conclusions.

This means that if you read Philosopher X’s deductive argument and you disagree with her conclusion, then you’re committed to the claim that her argument is unsound. Either X’s conclusion does not actually follow from her premises — there is a problem with her reasoning or logic — or at least one of X’s premises is false.

When you’re doing philosophy, it is never enough simply to say that you disagree with someone’s conclusion, or that their conclusion is wrong. If your opponent’s conclusion is wrong, then there must be something wrong with their argument, and you need to say what you think it is.

Terminology: The Philosophical Glossary discusses when to say someone “proved” something versus when to say they merely “argued for” it. The former words communicate that you think the author succeeded. The latter leave it open whether their arguments are convincing or sound:

You should not say that Locke has proven some claim, or shown or demonstrated that something is the case, unless you think that Locke’s arguments for his claim are successful. If Locke has proven a claim, then the claim must be true.

If you doubt or want to leave it open whether Locke’s arguments for a claim are successful, then you should say instead

Locke argues that…orLocke defends the claim that…orLocke tries to prove that…or something of that sort.

| Here are some sample arguments. Can you tell which ones are valid and which of the valid arguments are also sound? (There are 5 valid arguments and 2 sound arguments.) |

I. If Socrates is a man, then Socrates is mortal. Socrates is a man. So, Socrates is mortal. |

II. If Socrates is a horse, then Socrates is mortal. Socrates is a horse. So, Socrates is mortal. |

III. If Socrates is a horse, then Socrates has four legs. Socrates is a horse. So, Socrates has four legs. |

IV. If Socrates is a horse, then Socrates has four legs. Socrates doesn’t have four legs. So, Socrates is not a horse. |

V. If Socrates is a man, then he’s a mammal. Socrates is not a mammal. So Socrates is not a man. |

VI. If Socrates is a horse, then he’s warm-blooded. Socrates is warm-blooded. So Socrates is a horse. |

VII. If Socrates was a philosopher then he wasn’t a historian. Socrates wasn’t a historian. So, Socrates was a philosopher. |

Merely having a sound argument is not yet enough to have the persuasive force of reason on your side. It may be that your premises are true, but it’s hard to recognize that they’re true.

Consider the following two arguments:

Argument A

- Either God exists, or 2+2=5.

- 2+2 does not equal 5.

- So God exists.

Argument b

- Either God does not exist, or 2+2=5.

- 2+2 does not equal 5.

- So God does not exist.

Both of these arguments have the form P or Q. Not-Q. So P.

That’s a

valid form of argument. So both of these arguments are valid. What’s

more, at least one of the arguments is sound. If God exists, then all

the premises of Argument A are true, and since Argument A is valid, it

must also be sound. If God does not exist, then all the premises of

Argument B are true, and since Argument B is valid, it must also be

sound. Either way, one of the arguments is sound. But we can’t easily tell

which of these arguments is sound and which is not. Hence neither

argument is very persuasive.

In general, when you’re engaging in philosophical debate, you don’t just want valid arguments from premises that happen to be true. You want valid arguments from premises that are recognizable as true, or already accepted as true, by all parties to your debate.

Hence, we can introduce a third notion. This quality of argument doesn’t have a standard name, but we can naturally describe it like so:

A persuasive argument is a valid argument with plausible, or obviously true, or antecedently accepted, or sufficiently justified premises.

These are the sorts of arguments you should try to offer, and that you should expect to be given.

Their premises should be uncontentious — or at least, less contentious than the argument’s conclusion. If they aren’t obvious, they should at least be widely enough accepted by the parties to the debate, that they don’t need defending. Else the author has the responsibility to support or justify them — either with yet further argumnt, or in other, less conclusive ways.

In any event, an argument’s premises should be credible independently of its conclusion — in the sense that it’d be possible for someone to reasonably accept the premises even if they had not already accepted the conclusion.

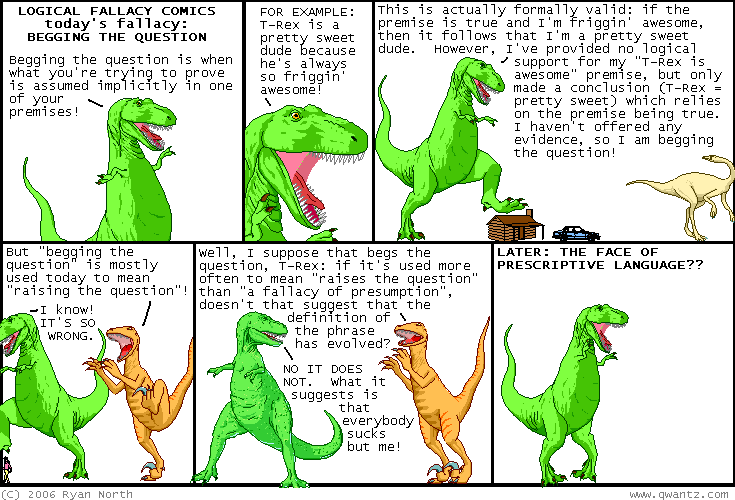

Begging the question is a technical philosophical label for arguments that fail to do that. These arguments assume or rely on the very point at issue in attempting to argue for it. This may also be called “circular reasoning.” Here is an example of an argument with this vice:

We know that God exists, because it says so in the Bible. And we can trust the Bible on this matter because it’s the Word of God, and so must be correct.

This argument begs the question because one of its premises says that the Bible is the Word of God. Presumably, one would only accept this premise if one already believed that God exists. But that’s precisely what we’re supposed to be arguing for!

A good rule of thumb is the following: if an argument contains a premise or step that would not be accepted by a reasonable person who is initially prone to doubt the argument’s conclusion, then the argument begs the question.

We will seldom see obvious cases of begging the question in our readings. It’s the unobvious cases of begging the question which are really dangerous, because they’re so hard to spot.

The funny label “begging the question” for this vice comes from old mistranslations of a Latin phrase that should have been translated as “claiming the question,” that is, trying to grab without argument the very answer whose correctness you’re debating.

Ordinary people have started to use the expression “begging the question,” too. Usually they don’t mean what philosophers do. They mean something like “prompting or inviting a question.” This started out as a misunderstanding of the philosopher’s notion, but eventually, if ordinary people keep using the expression that way, maybe that’s what it will mean, at least for them.

Deductive arguments contrast with non-deductive arguments in that the former are ones whose premises conclusively entail their conclusions. If you accept the premises as true, the conclusion cannot be avoided: it has to be true as well. However, often (perhaps always) we won’t be in positions where the premises of an argument are absolutely indubitable and immune to philosophical challenge. So although we’re working with deductive arguments, these arguments usually won’t decisively settle the debates we’re considering. We’ll have to sort out how plausible and convincing different arguments’ premises are, to assess how much persuasive force those arguments should have.

We’ll discuss these issues more later.

This page tried to explain, and enable you to understand, the following concepts: