Bouwsma's Verificationist Response

In The Matrix do you think it's bad to be inside The Matrix program? If so, what makes it bad? The character Cypher prefers living inside the comfortable program to living in the harsher real world. He wants to get plugged back into the program and have all his memories of the outside world erased, so that he can be blissfully unaware that it's all an illusion. He figures, what he doesn't know won't hurt him. Is he making the smart choice here? Or is he making a foolish and cowardly choice? What do you think?As I said at the start of term, we ordinarily distinguish between what's true and what we know or can know to be true.

If I draw a squiggle on the blackboard, and then erase it, the squiggle had a certain length, even if none of us know or ever will know what that length was. What it takes for the squiggle to be 3 m. long is one thing, and what it takes for us to have evidence that the squiggle was 3 m. long is something else. That's our ordinary, realist view of things. Material objects (like my chalk squiggle) exist independently of what we think about them and what experiences we have. They would still have existed even if there hadn't been any people. And what properties they have is independent of what beliefs and evidence we have.

The verificationist is someone who rejects that realist view. The verificationist thinks:

If something is true, then it has to be possible to know or verify that it is true.

According to the verificationist, it doesn't make sense to talk about something's being true even though nobody knows or could know that it's true. It only makes sense to talk of our being wrong when it's in principle possible to detect that we are wrong. So the kinds of systematic and undetectable illusions the skeptic is imagining--with dreaming or being a brain in a vat--it is not really possible for us to be systematically deceived in those ways. According to the verificationist, if everything seems real to us in every respect, if all our evidence says that it is real, then it is real. All there is to something's being real is its seeming real in every respect. That's the view that Bouwsma wants us to accept.

Now, does it really seem plausible that the facts about, say, Mt. Everest's height, have anything to do with us and what we have evidence for believing? On the face of it, that's grossly implausible. Indeed, it seems arrogant and ridiculous to think that Mt. Everest's height depends upon us, in the way the verificationist thinks it does. This makes one want to look very closely at the verificationist's arguments for his view, to make sure that he's not trying to pull the wool over our eyes.

You should read the selections from van Inwagen's book, where he talks about "The Common Western Metaphysic" and the notion of "objective truth." The view that van Inwagen calls "anti-realism," and argues against, is the same as the view we're calling "verificationism."

As van Inwagen points out, the character O'Brien in Orwell's Nineteen Eighty-Four espouses a verificationist picture of reality. According to O'Brien, The Party controls people's memories, so they control the past. If they make everyone think that the past happened a certain way, and they destroy all the traces of things happening a different way, then the past really did happen the way The Party says it did. This is a pretty strange view of reality. Ordinarily, we think that there are objective facts about what the past is like, and what the external world is like, which are independent of what anyone believes or knows about them. The Party can say whatever it likes about the past. If such-and-such people were really in New York on a given day, then they really were there, and nothing The Party says or gets us to believe will change that.

As I mentioned at the start of term, sometimes people think that if you talk about objective facts, then you're saying that you know what those facts are, and that you're in a better position to know what they are than other people. I emphasized that this is not something you're committed to, just by talking about objective facts. Van Inwagen also emphasizes this in his discussion.

The realist says that what it is for there to be mountains of such-and-such a height, what it is for such-and-such people to have been in New York on a given day, these things have nothing to do with us and our epistemic powers. That's all the realist is committed to. That is compatible with going on to say:

- there are mountains of such-and-such a height, and we know that there are.

But it's also compatible with going on to say:

- there aren't any mountains, but if there were mountains, what that would involve would be stuff in the world that's independent of our beliefs and knowledge.

And it's even compatible with the skeptic's view that:

- we can't know whether or not there are any mountains.

All three of those views are realist views. They're all realists because they think that what it is, or what it would be, for there to be mountains of such-and-such a height, is a matter of how certain piles of rock are configured, and has nothing to do with us and what we can believe or know. (Well, we wouldn't call someone who denies that there are mountains a realist about mountains. But he holds a realist picture of the world, because he thinks that what it would take for there to be mountains has nothing to do with us and what we know or believe.)

The verificationist or anti-realist, on the other hand, thinks that whether there really is a mountain of a given height does depend on whether we know or can know there to be such a mountain. He says that:

- if it seems to us in every respect as if there's a mountain there, then there has to be a mountain there. It's not possible for us to be systematically deluded about such things.

What kind of argument could persuade one to accept this verificationist view?

- There are a number of clever rhetorical tricks, and subtle misdirection, in Bouwsma's article.

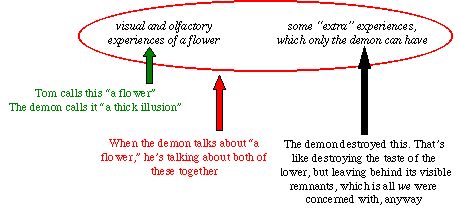

On pp. 149-50, Tom tells the evil demon that the disagreement between them amounts to this:

Tom says: if the imperceptible "reality" that the demon destroyed was forever inaccessible to us anyway, then what concern can it really be of ours? What the demon (skeptic) is denying us knowledge of is nothing we had ordinary commerce with or interest in, in the first place.

That is an extremely subtle move for Bouwsma to make. Of course, in the picture Tom describes, we shouldn't be very bothered about the stuff that the demon destroyed. So if Tom has presented his disagreement with the demon accurately, then it does seem like Tom has the more sensible position.

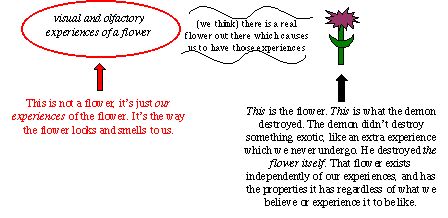

But a realist would characterize the disagreement between Tom and the demon differently. On the realist picture, things look like this:

And here it does seem like the demon has managed to take away something we were ordinarily concerned with.

Bouwsma hasn't really given any argument for accepting his view, instead of the realist view. He's just demonstrated that, if you think of things in his way, then you won't think of the skeptic as posing much of a threat. But by itself that doesn't cut much ice. Ordinarily we don't think of things in the verificationist way that Bouwsma does. Ordinarily, we find it much more natural to think of the world the way the realist does. If we're going to give up that realist picture, we need to see a real argument for doing so.

- There are arguments for verificationism. Many of the philosophers who adopt verificationism do so because they think it's impossible for the realist to avoid skepticism. They think the realist has no good response to the skeptic's arguments, and that it'd be better to give up the realism than to succumb to skepticism.

Well, this whole class will be concerned with the question whether it really is impossible for the realist to avoid skepticism. I hope you will agree that it's important for us first to get a clear understanding of what a realist's theory of knowledge would look like, and what the realist's options are for responding to the skeptic, before we give up on realism and decide to become verificationists. Those are the questions that we will be pursuing in this class.

- There are other arguments for verificationism, too, that come from the philosophy of language and from philosophy of mind. We won't get into those arguments here, but you may deal with them in other philosophy classes.

So far, I have been emphasizing how alien the verificationist's view of the world is to our ordinary ways of thinking. To be sure, that is no proof that verificationism is incorrect. But it does put the burden of proof on the verificationist. It seems like the most sensible way for us to proceed is to assume that our ordinary, realist picture of the world is correct, until we encounter good arguments that persuade us otherwise. That is the main consideration against verificationism that I want us to rely on in this class.

There are also a number of technical problems with verificationism, that make it unclear whether verificationism is even a stable, internally coherent philosophical view. One of these problems has to do with the status of verificationism itself. The verificationist says that there are no objective truths, that all truths depend somehow on our being able to have evidence or knowledge that they are true. What is the status of that claim? Is it objectively true? If so, then wouldn't there be trouble, because the verificationist says that there are no objective truths. Or is verificationism itself something which is only true if we can have evidence or knowledge that it is true? Well, then, what would the evidence be? What sorts of things might be evidence that verificationism is true, rather than realism? If there could be evidence of that sort, then couldn't the evidence also go the other way, and support realism as opposed to verificationism?

There are many other technical problems with verificationism, too. I don't want us to get too bogged down in those problems in this class. We're just going to focus on the considerations I mentioned above, that realism seems a more natural picture of the world to us, so the burden of proof is on the verificationist. Also, as I said, even if you want to give up realism, it's important to have a clear understanding of what the realist's theory of knowledge will look like. And that's what we're going to focus on in this class.

URL: http://www.courses.fas.harvard.edu

Last Modified:

Copyright © The President and Fellows of Harvard College