A mental state is a kind of property that can only be found in thinking, feeling creatures. They are conditions your mind can be in, that explain or are expressed by what you do and say and feel and notice and decide. They are what make up your “mental life.” In some cases, we call these properties mental events; in other cases, we call them attitudes.

Some examples are:

There are a couple of categories philosophers use to describe these states, to help us make conceptual maps of them.

In class I mentioned a conceptual map that Plato proposed (between the rational part of the soul, the spirited part, and the appetitive part). Also a conceptual map that Freud proposed (between the superego, the ego, and the id). The details of their maps aren’t going to be important for our discussion. But one thing to notice about their maps is that they’re supposed to be exclusive and exhaustive categories. That is, mental states in one of the boxes can’t at the same time also inhabit any other box. (That’s what’s meant by calling the categories “exclusive.”) And every mental state belongs in one of the boxes or another. (That’s what’s meant by calling the categories “exhaustive.”) But it might sometimes be hard to figure out which box a given mental state is supposed to inhabit.

We’re going to propose some categories that will be helpful to use in our discussions this semester. Unlike Plato’s and Freud’s, our categories may not be exhaustive, and importantly, they may not be exclusive either. We’ll see that some mental states seem to bridge more than one category.

We’ll present two contrasts: first, between episodic and dispositional mental states, and second, between representational and qualitative mental states. As we’ll discuss, these contrasts are somewhat related but not the same.

Episodic states are “happenings” taking place in your mental life, that you could direct your attention to. They occur, last some stretch of time, and then stop. Examples include feeling an itch right now, or imagining a pentagon. Or being annoyed for the last ten minutes. Or playing back a memory in your mind’s eye, like your memories of what happened and how you felt on your first day at UNC. Or a silent conversation you have with yourself. Or thinking through the verses of a familiar song. Or “daydreaming.” Or feeling nervous during an exam.

Other words used to describe these parts of your mental life are mental events, processes, or occurrences.

Something common to all these states is that when they’re over, they’re no longer “present right now” in your mind to direct your attention to anymore. Of course, many of them could be repeated. Maybe you have the same silent conversation with yourself every morning. Or maybe that darn itch keeps showing up, going away for a while, and then coming back.

Some of these mental episodes stay the same throughout their duration (like that darn itch). Others can’t be present all at once, but instead progress through stages (like my silent conversation with myself, or the silent rehearsal of a song).

Some of these mental episodes are short (a feeling of surprise), but others can last a long time (feelings of grief).

When we talk about a disposition, we mean a tendency or capacity or potential something has to be a certain way. But it need not be activated right at this moment.

We can talk about dispositions that aren’t mental: for instance, a soap bubble may be disposed to pop even though it hasn’t popped yet. Humans are disposed to float more easily in water than gorillas.

We can also talk about mental dispositions. These are properties of your mind, but they’re more “in the background” than mental episodes are.

For example, you may be honest, and witty, and generous, and obsessive. Those are all mental dispositions. All of those descriptions may be true of you at this very moment — even though you’re not talking to anyone, so not exercising your honesty and wittiness. Having a favorite color also seems dispositional, as it may be that you have one, but you aren’t doing anything right now to act on or express that preference. Your values and commitments seem also to be dispositional.

Having these properties isn’t or needn’t be about what’s happening to you right now. Instead, they’re more like “standing tendencies” or readiness: you’re the kind of person who would think/feel/act in certain ways if the situation came up.

These dispositions show up in what you would do or think in the right circumstances, not necessarily in what you’re consciously undergoing at the moment.

Another example: knowing how to ride a bike. You aren’t riding right now, but you have an ability you can exercise when needed.

Or being afraid of dogs. You might be perfectly calm right now, but if a dog approached, you’d tense up, avoid it, interpret barking as threatening, etc.

Note that “dispositional” doesn’t mean the same as “unconscious.” A dispositional state might be something you could easily bring to mind, but you’re just not currently thinking about it.

Episodic mental states are a matter of what’s going on in your mind during some stretch of time. What are you feeling or experiencing right then?

Dispositional mental states are a matter of what your mind is set up to do across situations, even when nothing is currently happening.

How are those two categories related?

The clearest examples of episodic states, like an itch, don’t seem to have much to do with how you’re disposed to act or think in other situations. They just seem to be a matter of what’s going on in your mind right at that moment. The clearest examples of dispositional states, like honesty or generosity, might not have much to do with what episodes of thinking or feeling you’ll have. They just have to do with how often you tell the truth or give others your time or resources.

But one complication is that dispositional states do often show themselves through episodic ones.

If you’re afraid of dogs (dispositional), you might have feelings of fear (episodic) when a dog approaches.

If you believe it’s going to rain (dispositional), you might at some point think to yourself “it’s going to rain” (episodic), feel concern (episodic), or reach for an umbrella (this is an action involving both your mind and your body).

But dispositional states can still be there even when none of those episodes are occurring.

Some kinds of mental states seem hard to categorize.

We might count your beliefs as a matter of how you’re disposed to think and react; but we could also see them as judgments or affirmations that you make when you talk to yourself (episodes).

We might count knowing how many sides a pentagon has as a disposition (to come up with the right answer); but we could also count it as a confident thought that you have (an episode).

Similarly with remembering that Carolina was founded before 1900.

You could see episodic elements to these states (what thoughts will be running through your head at a given moment), and also see dispositional elements to them.

Philosophers are still arguing and sorting out how to think about these matters.

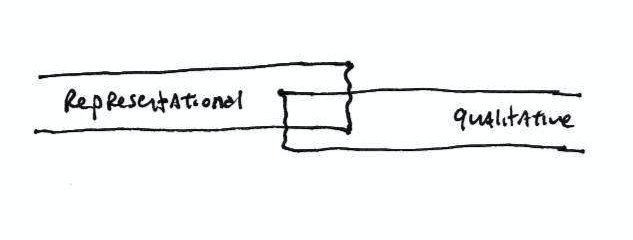

So I will diagram these catgories like this:

The squiggly borders on the right side of “dispositional” and on the left side of “episodic” mean that it’s controversial and unclear where the categories end. Maybe the categories don’t overlap after all. But many thinkers think that they can overlap, that is, that some kinds of mental states are both dispositional and episodic. Or that they have both dispositional and episodic “faces.”

Next we’ll consider a second pair of constrasting categories.

Many mental states are representational or as philosophers sometimes also say, intentional. (We’ll talk about this use of the word “intentional” later.) What this means is that they’re about things. Philosophers also sometimes describe this in terms of the states having content.

For instance, consider the true belief that Charlotte is south of Carrboro. This belief is about Charlotte and about Carrboro. The false belief that Charlotte is north of Raleigh would also be about Charlotte.

Many representational states concern the possibility of things being one way rather than another. For instance, the belief that Charlotte is south of Carrboro concerns Charlotte being located in one place rather than another. My wish that I could dance like Fred Astaire concerns my dancing one way rather than another. We call these states propositional attitudes. A proposition is the sort of thing that can be true or false, and can be believed or denied. It’s what philosophers usually mean when they talk about “the content” of a mental state. Charlotte is south of Carrboro and I dance like Fred Astaire are two examples of propositions. A propositional attitude is a kind of “mental stance” or relation you take towards a proposition. In the first example, you believe the proposition to be true. In the second example, I wish that the proposition were true.

Other examples of representational states: hoping that something is true, expecting it will be true, fearing that it will be true, being angry or happy or disappointed or relieved that it’s true.

Some philosophers count knowing that something is the case (or remembering that it’s the case) as propositional attitudes too, even though you can only know/remember that something happened if it really did happen. That is, these are attitudes you can only have towards true propositions or facts.

When we talk about representational states in this class, we’ll mostly be concerned with propositional attitudes. It’s controversial whether there are any representational states that aren’t propositional attitudes. Some candidates for being such are states like this:

For these examples, understand the state to be focused on the general possibility of a pony (any pony). Not some specific ponies living up the street.

These examples would also make sense if we replaced “pony” with “troll”. You can want, and imagine, and seek things that don’t exist.

In examples like this, since there’s no specific pony you’re thinking about, ponies are called “intentional objects” of the state. Some philosophers have argued that these states can all be “reduced to,” or explained in terms of, facts about what propositional attitudes you have. For example, wanting a pony might be a matter of wanting that you own a pony. Fearing ponies might be a matter of fearing that some pony will chase you and eat you up. Or something like that. Other philosophers argue that these examples can’t be reduced in this way. This controversy remains unsettled.

Representational states of either sort have important characteristics that we should keep track of.

They can be “incomplete” in certain ways. They need not specify every detail of the objects they’re about. Consider my memories of my first-grade teacher. These memories do not represent her as having brown eyes. But they do not represent her as having non-brown eyes either. I cannot remember the color of her eyes. The mere fact that some representational states represents an object, and fails to represent it as being F, does not entail that the state represents the object as being not-F. There is a gap between “not-(representing it as F)” and “representing it as (not-F).”

Here’s another way that representational states needn’t specify every detail: they can represent things about an F, without there being any specific or particular F they are about. In our examples, a needy child desires a pony (or that he have a pony) without there being some specific, already existing pony such that his desire is for that pony.

As we said, representational states can also represent things about an F, even though no Fs ever have or ever will exist. Our child may fear trolls, or believe that there is a troll hiding under her bed, even though no trolls ever have or ever will exist.

Representational states can represent the F (or represent that the F is a certain way), and fail to represent the G in the same way, even if the F is the G. For instance, Lois Lane believes that the super-hero who defends Metropolis is strong. But it doesn’t seem like Lois believes that the mild-mannered reporter at the Daily Planet is strong. Yet the super-hero who defends Metropolis (Superman) is the mild-mannered reporter Clark Kent at the Daily Planet. We’ll describe this by saying that Lois’s beliefs have a perspective on Superman, and she believes things “through” that perspective; she might not believe the same facts if she encounters them “through” a different perspective. We’ll talk about these ideas again later in the course.

Contrast Lois’s beliefs to other, non-representational, relations she might stand in to Superman. If she kisses the super-hero, and the super-hero is the same person as the reporter, then it follows that she kissed the reporter, too. If she kicks the reporter in the knee, and the super-hero and the reporter are the same person, then it follows that she kicked the super-hero in the knee, too. Representational states seem different. If she believes the super-hero is strong, it’s not clear she has to believe the reporter is strong; even though they’re the same person. If she wants to marry the super-hero, it’s not clear she has to want to marry the reporter. And so on.

Another category of mental states goes under many different names. Some of them are:

Some examples of states with these properties are: pains, tickles, experiences of tasting salt or holding a melting ice cube, experiences of seeing colors, and so on.

These kinds of states are understood to be conscious, and such that there’s some distinctive way it “feels” to be in that mental state. There is no special way it feels to be 6 feet tall, on the other hand. The statue is 6 feet tall, but it doesn’t feel anything. Joe and Terry might both be 6 feet tall, but have very different feelings. There is a special way it “feels” to be in pain. Everyone who is in pain feels the same way. Of course, we can be more specific and fine-grained, and talk about stabbing pains versus dull throbbing pains versus other sorts of pain. But for each of these, there will be some distinctive way it feels to have that sort of pain.

The same goes for perceptual experiences. When I look at a ripe tomato, I have a certain kind of visual experience, and there is a distinctive conscious character to this experience. Everyone who has the same experience will also have that distinctive conscious character. (Let’s leave it an open question whether you also have this same experience when you look at ripe tomatos. Maybe you have a different kind of experience, one that I’d associate with the word “green.” But if you have the same experience that I have, there is a distinctive conscious character that you must be having.)

When mental states have a distinctive conscious character like this, we say that they are qualitative states or phenomenal feels, and we call their distinctive “feel” or conscious character their qualitative character. (Or we use some of the other labels above.)

It is a major question in contemporary philosophy of mind how exactly we should understand and explain these notions.

Part of the controversy concerns what the relation is between qualitative states and representational states.

Everyone agrees that there are some representational states that are not qualitative. For instance, there is no distinctive way it feels to have a given belief. I may feel a certain way when I believe that Charlotte is south of Carrboro, but you may have the same belief and feel a different way, or have no special feelings at all.

Philosophers sometimes distinguish between (a) judging or episodically / occurrently thinking something to yourself, and (b) believing something, where this is essentially tied to how you’re disposed to act and/or talk, and what inferences you’re ready to make. Some may count (a) as one kind of belief, others may not. There’s debate about whether (a) does or doesn’t always involve a distinctive qualitative feel. When I say “everyone agrees,” I’m talking about (b). Everyone agrees that it’s possible to have (b) without there being any distinctive qualitative feel to the belief.

There the agreement runs out. A few philosophers think that the set of representational states and the set of qualitative states are entirely separate or “disjoint.” They do not overlap at all.

Other philosophers think that some qualitative states, for example perceptual experiences, are also representational states. Some count them as propositional attitudes — you see that something is the case. Others count them as states with intentional objects — you see a pony — and argue that we only get propositions when we form beliefs on the basis of what we see. But these philosophers also think that there are qualitative states, like pains and bodily sensations, that are not representational.

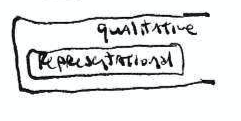

So I will diagram these catgories like this:

The squiggly borders on the right side of “representational” and on the left side of “qualitative” mean that it’s controversial and unclear where the categories end. Maybe the categories don’t overlap after all. But many thinkers think that they can overlap, that is, that some kinds of mental states are both representational and qualitative.

Still other philosophers think that qualitative states just are a certain kind of representational state. So every qualitative state is a representational state (though as we said, there are also representational states like belief that aren’t, or aren’t always, qualitative).

Those philosophers would diagram the categories like this:

There are even some philosophers who think the situation is reversed: that (genuinely) representational states are always qualitative, but that some states are qualitative without being representational:

I want to acknowledge that these controversies exist; but we’re not going to try to settle them in our course.

Qualitative states are probably always episodic. They are a matter of what’s going on in your mind right now.

And many philosophers would say that representational mental states always have some dispositional aspect to them.

But as we said, it may be that some representational mental states are also qualitative, and so would also be episodic.

Some philosophers would argue that representational mental states can be episodic even if they’re not qualitative.

It’s not clear that the categories we’ve described capture every aspect of our mental lives. Some examples to think about are actions and abilities, Often these involve the participation of your body as well as your mind, as when you lower your arm on purpose. But there can also be wholly mental actions: for example, when you (silently, to yourself) count how many letters in the alphabet come before “h.” Some abilities, like solving puzzles and using language, also seem to be more mental than physical.

When we talk about abilities, it sounds like we’re discussing something dispositional: you can have an ability even if you’re not exercising or making use of it right now. But at the same time, there seems to be more to having an ability than just being disposed to respond some way. I might be disposed to cringe and feel anxious when I hear the sound of nails on a chalkboard: but that doesn’t make it an ability I have. It’s a reflex. Abilities seem to have more to do with my choice and control.

When we talk about actions, it sounds like we’re discussing an event or occurrence or happening, so this sounds like a mental episode. But even when we consider only those actions that are purely mental, it’s not clear that its being an action of mine, rather than just something that happens to me, is just a matter of what I think and feel while it’s taking place. Maybe it can only be an action if I have the corresponding ability?

Later in the course, we’ll be thinking more carefully and asking questions about actions and abilities.

I’ve moved this material to a separate page.

There have been various attempts to find a single feature or set of features that all mental states, processes, qualities and so on have, and that all non-mental states and so on lack. If we found such features, they would be marks or criteria for mentality.

However, so far none of these attempts has been successful. Or more accurately, none of them has met with uncontroversial success. For each proposal, it is controversial whether all and only mental states have the proposed mark.

One proposal is that being representational is a mark of the mental. But qualitative states (pains, tickles) are clearly mental states. And as we said, it is controversial whether every qualitative state is also a representational state.

Another difficulty with this proposal is that some things that we wouldn’t naturally count as mental also seem like they can represent other things. One example is words in the newspaper, representing next week’s weather. Another example are rings in a tree trunk, representing how old the tree is.

With some of these examples, like the newspaper, it’s arguable that their representational power derives somehow from the fact that people whose minds can represent agreed to use the words that way. So perhaps mental representations are in some way more fundamental than newspaper representations. But even if that’s so, it’s not clear how to turn it into a successful refinement of the proposal that being representational is a distinctive mark of mental states. It also doesn’t address the issue with tree rings.

Another proposal is that being conscious is a mark of the mental. This would include all of our qualitative states, and perhaps it could also include things like our conscious judgments or beliefs. (The philosophers who doubt whether those lack a distinctive qualitative feel may still allow that they’re conscious in some sense.)

It is extremely difficult to understand and explain what “being conscious” amounts to, so this proposal is hard to assess. But on the face of it, there do seem to be examples of mental states that aren’t conscious. For example, arguably you believe some propositions you’ve never consciously formulated and thought about. Consider the example I’ve never ridden a pony and an elephant at the same time. That’s probably not news to you. In other words, you already believed it, before you heard or read me saying it. You just never consciously said those words to yourself.

So this proposal is also controversial. It seems like there can be some mental states, such as some of your beliefs, that aren’t conscious. Freudian psychologists think there are many of these.

Our third proposal has to do with the different ways that our mental lives are thought to be uniquely private, that is, you have a kind of special or priveleged access to your own mental life.

I’ve moved this material to a separate page.

As I said, it’s very hard to come up with a good account of what all mental states have in common, that makes them mental. Nobody has yet come up with a simple, definitive, and uncontroversial story about this. For each mark that has been proposed, we can find mental states that — at least according to some philosophers — don’t possess that mark. (And sometimes we may find non-mental-states that do possess it.)